Introduction to Knee Arthritis

Have your knee arthritis symptoms become so severe that your current medication and management regimen is no longer working for you? Do you want more information to help you better manage your knee health and mobility? We have found that for many people in this situation, good information is hard to come by. It is either too basic for someone who has been living with arthritis for a number of years, or focused on medical professionals and too complicated and full of jargon. This guide will provide simple, reliable information to help you better understand what happens in your knee as your joint degenerates during the later stages of arthritis as it progresses towards tricompartmental osteoarthritis. For advice on how to deal with these symptoms it is best to seek professional medical opinion. If you plan on seeing a doctor to assess your knee health and changing needs, but want to become more informed this would be a good place to start! This guide is based on common questions about severe knee arthritis. We answer them where possible, and guide you to the best people to answer specific questions you have about your condition.

What is Happening to my Knee?

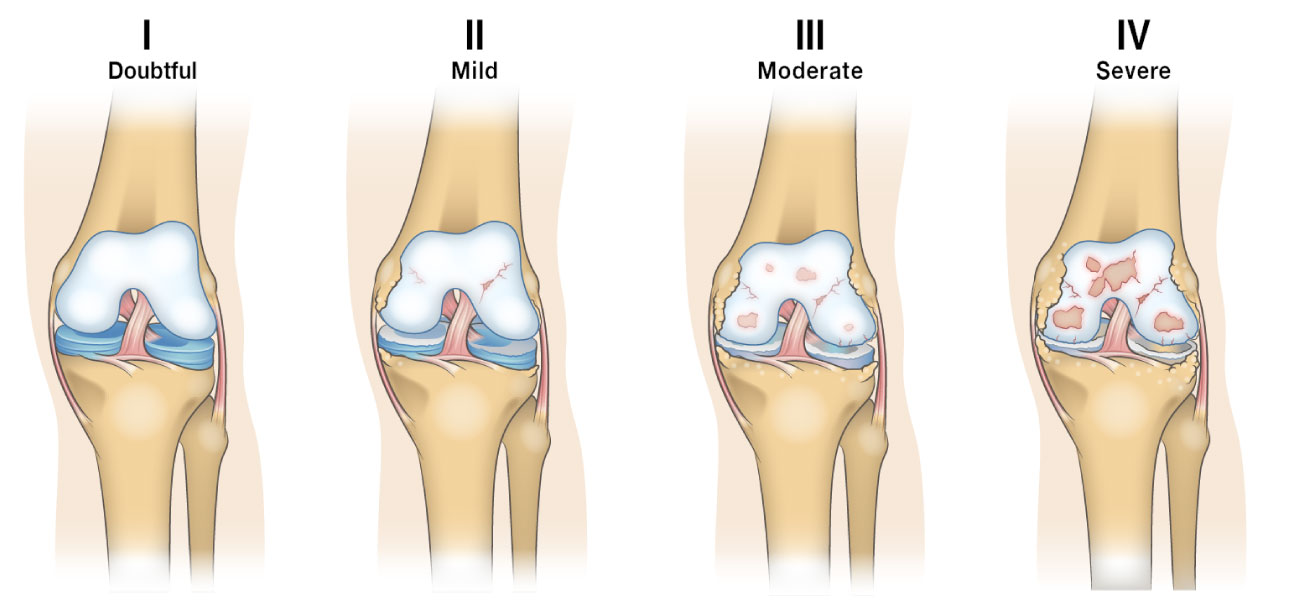

When osteoarthritis is in the more advanced stages there are many common physiological signs of joint degeneration that can occur. In this section we will outline the most common ones to help you better understand what is happening in your knee.

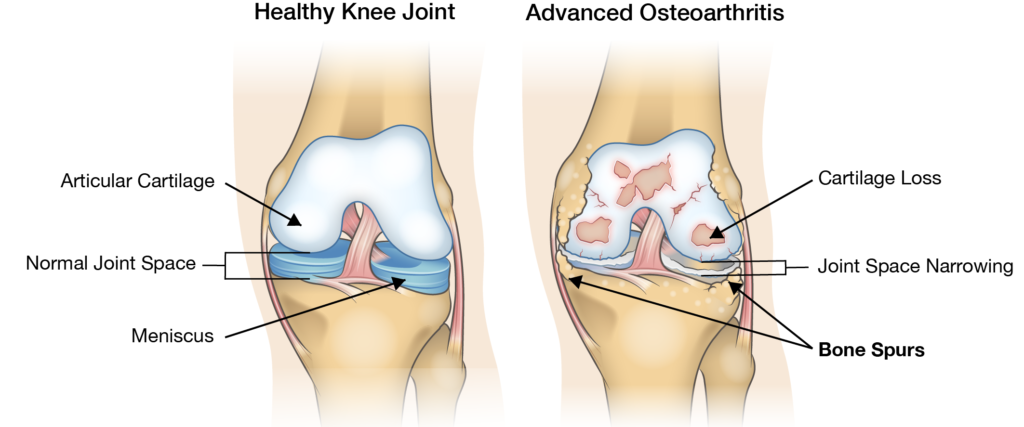

Cartilage Loss/Joint Space Narrowing

Cartilage loss is one of the primary markers used in the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. People with knee osteoarthritis can experience close to double the amount of degradation compared to the level of cartilage loss in a healthy knee over the same period of time. This cartilage loss causes the space between bones in the knee joint to narrow and can lead to bone-on-bone contact in the knee, often causing severe pain and discomfort. The rate of cartilage loss varies widely among individuals so it is difficult to predict how quickly it will wear away for any one person. During everyday activities like walking, crouching, or getting up from a seated position the forces acting at the points of contact between the joints can be up to three times greater than body weight. During a squat, this number approached seven times body weight. When the bones no longer have the cushioning provided by cartilage this can cause intense pain during these activities.

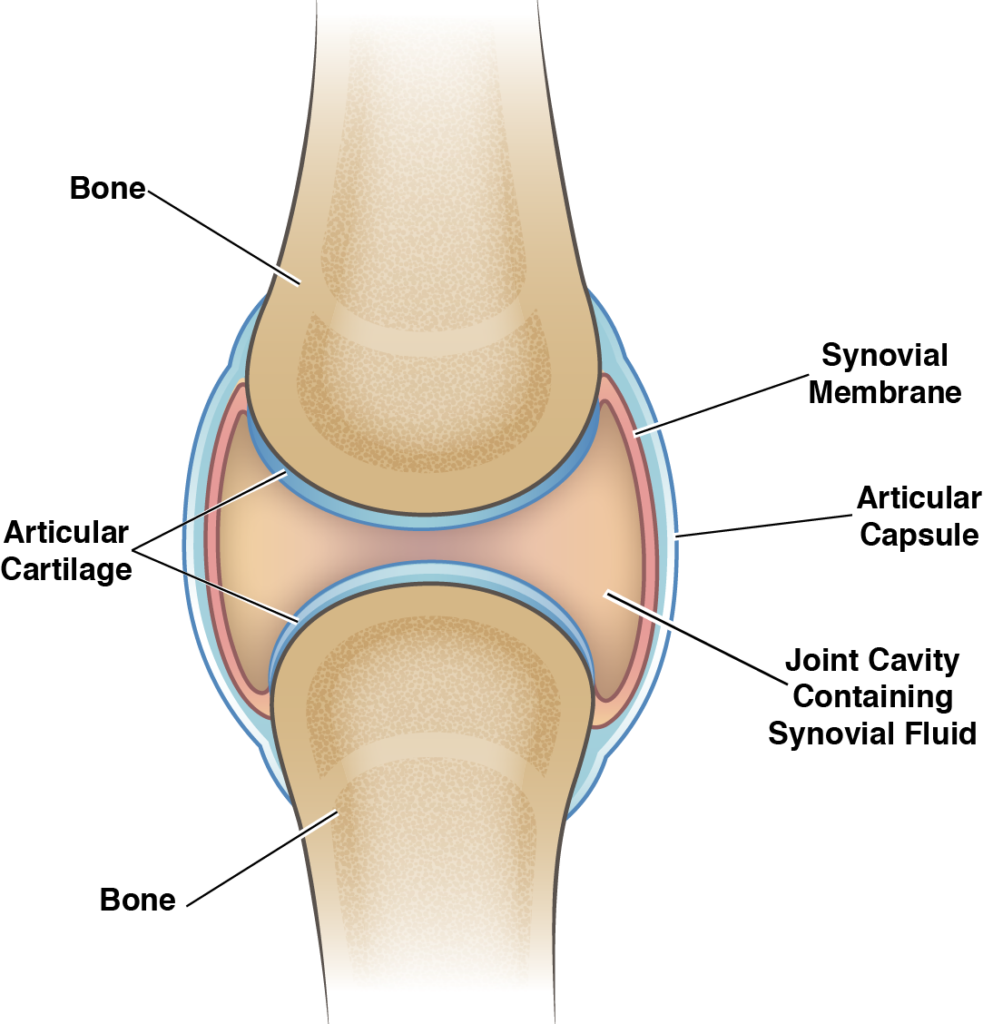

Change in Synovial Fluid

Synovial fluid is the natural lubricant that fills the joint. It allows for smooth movements, keeps the joints separated, and acts as a filter for the joint allowing the passage of nutrients while keeping out harmful substances. In cases of severe knee osteoarthritis, the synovial fluid becomes more watery and less effective as a lubricant for the joint. This causes more friction and overall wear and tear and is one of the main contributors to the cartilage loss discussed above.

Osteophyte Formation

When cartilage loss is at a point where bone-on-bone contact occurs there is often excessive bone growth in the affected compartment. These bone growths are called osteophytes (or “bone spurs”). Osteophytes can cause stiffness in the affected joint and can cause pain if they put pressure on nearby nerves. They are also often associated with misalignment of the affected knee, a common symptom of late-stage knee osteoarthritis.

Inflammation

Osteoarthritis has historically been classed as a non-inflammatory type of arthritis when compared to rheumatoid arthritis, but studies in the last decade have led to that view being reassessed as new evidence comes to light. The synovium (the area containing synovial fluid in the joint) is an area commonly affected by inflammation for people with osteoarthritis. Inflammation is usually characterized by redness, swelling, pain, and increased temperature in the area. Inflammation is caused by factors associated with osteoarthritis triggering the body’s natural immune response.

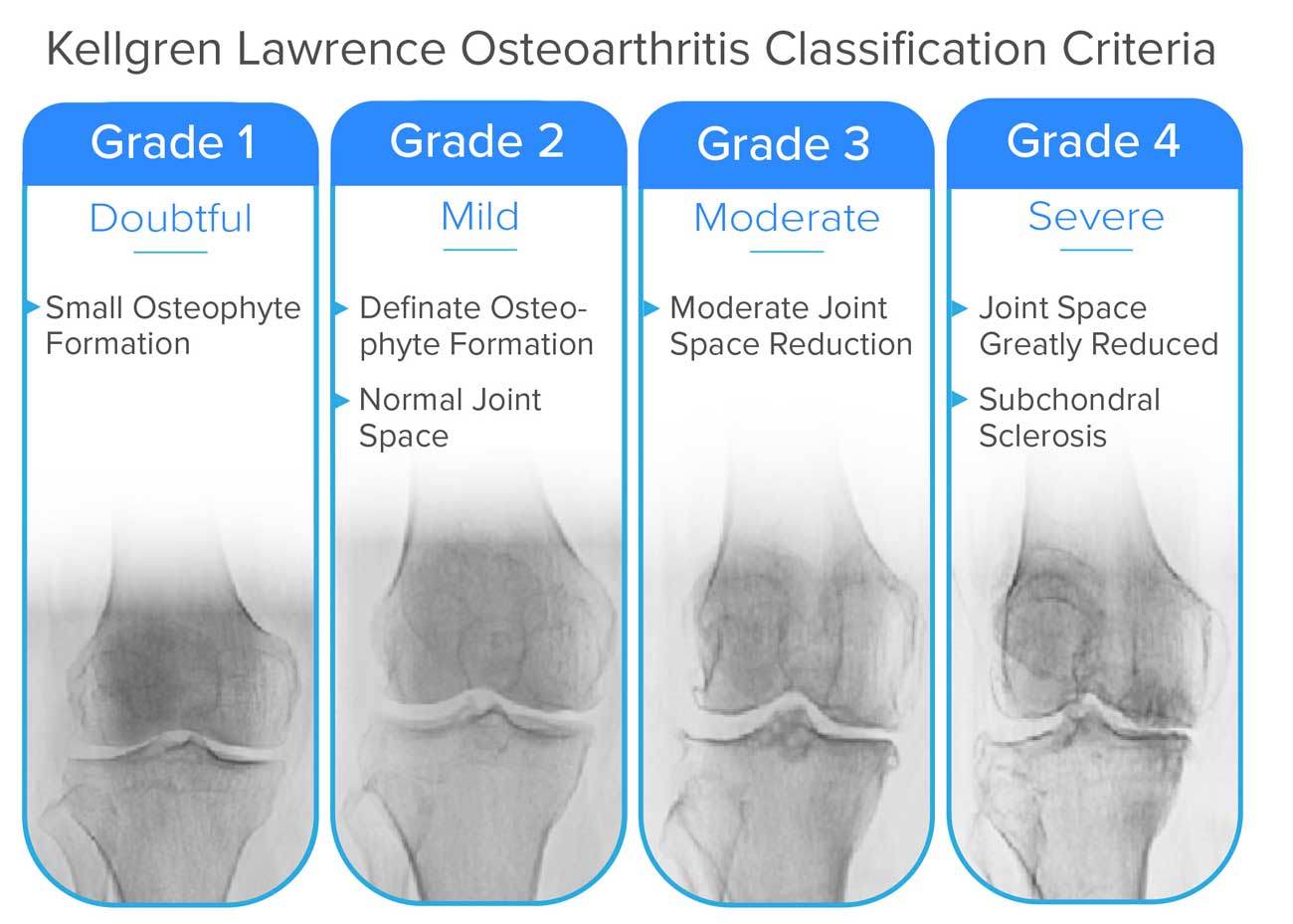

How does the condition change over time?

The Kellgren-Lawrence Classification of Osteoarthritis is a common system for describing the stages of knee osteoarthritis. Kellgren-Lawrence classification measures the progression of knee osteoarthritis in terms of joint space narrowing (JSN). The stages range from 0 (Normal space between the joints) to stage 4 (No space between the joints causing bone on bone contact and the growth of osteophytes). When discussing late stage or advanced knee osteoarthritis, it is usually in reference to those at stage 3 or 4 of the Kellgren-Lawrence classification system. In late stage knee osteoarthritis, there is little to no separation between the bones remaining. This can lead to very different symptoms from those experienced by people at earlier stages of the condition. When these bones freely grate together they often cause more severe pain and stiffness. This also leads to reduced mobility in many cases.

Are there different types of knee osteoarthritis?

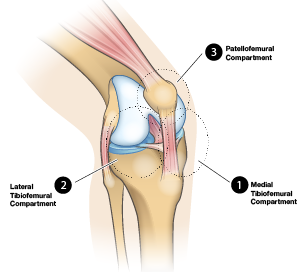

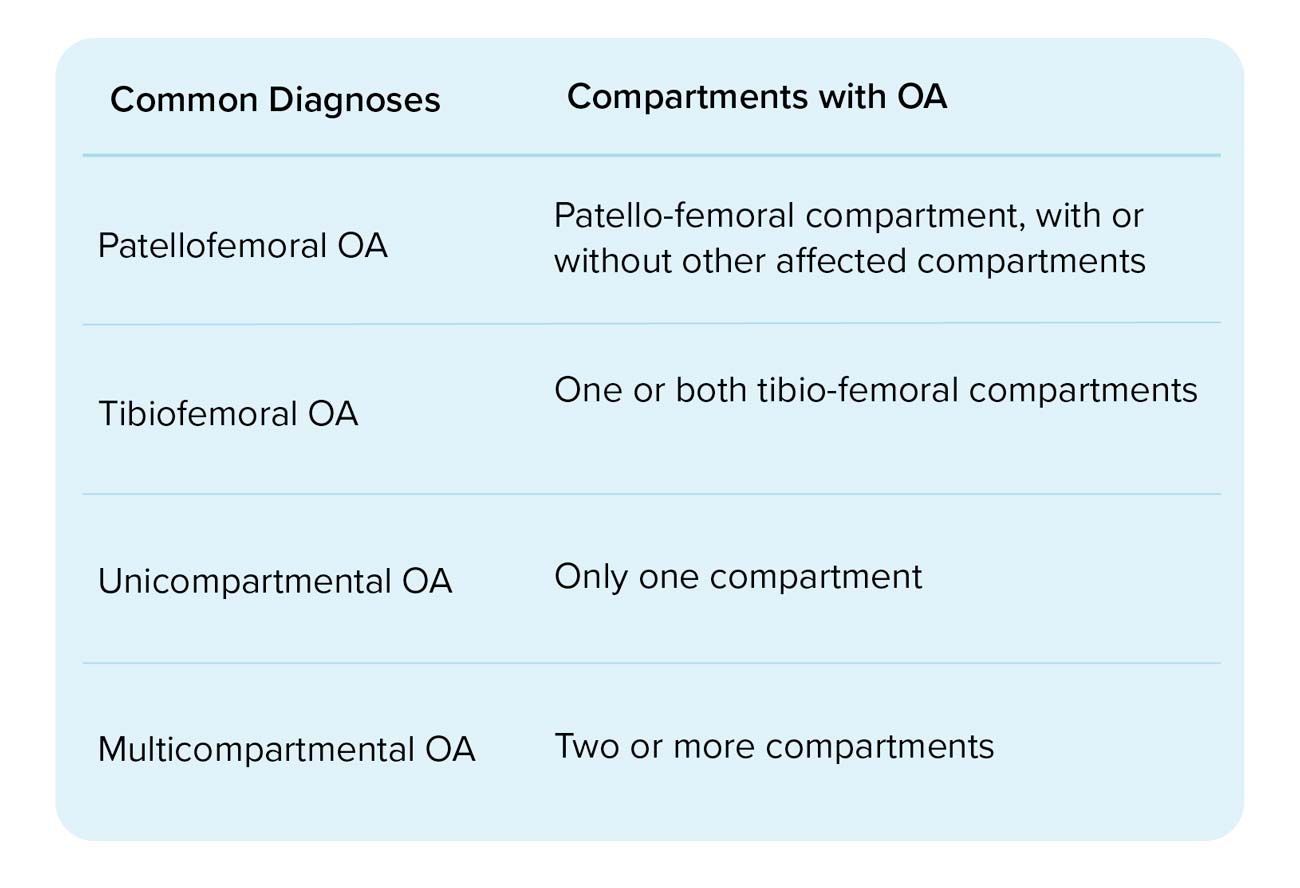

The knee has three contact zones, also known as “compartments” where osteoarthritis usually occurs. A common way to classify knee osteoarthritis is by which of the three compartments of are affected:

- Medial Tibiofemoral Compartment – the inside part of the knee where the tibia (shin bone) meets the femur (thigh bone).

- Lateral Tibiofemoral Compartment – The outside part of the knee where the tibia (shin bone) meets the femur (thigh bone).

- Patellofemoral compartment – The front of the knee between the patella (kneecap) and femur (thigh bone).

Depending on the individual any combination of these compartments could be affected. Understanding which areas of your knee are affected is key in helping manage the effects of osteoarthritis on the rest of the joint. Unicompartmental Knee Osteoarthritis – When a single compartment of the joint is affected. This could involve either the lateral or medial tibiofemoral compartment, or the patellofemoral compartment. Osteoarthritis of the medial tibiofemoral compartment can also lead to bone-spurs (small fragments of bone) near the affected area which can lead to a varus deformity (commonly referred to as bow-leggedness). A similar process can occur in the lateral compartment which leads to a valgus deformity (knock-kneed). Bicompartmental Knee Osteoarthritis – When two compartments of the joint are affected. This could be both tibiofemoral compartments, or a single tibiofemoral compartment and the patellofemoral compartment. Bicompartmental osteoarthritis occurs more commonly in the patellofemoral compartment and a tibiofemoral compartment that it does in both tibiofemoral compartments. Tricompartmental Knee Osteoarthritis – This is when all three compartments of the joint are affected. It is relatively common and most osteoarthritis knee braces are not designed to help with this condition.

Estimates of how common osteoarthritis is in each compartment of the knee vary quite widely. A study published by Oxford University found that of a group of subjects with radiographic knee osteoarthritis (can be detected by X-ray):

- 59% had osteoarthritis in both the patellofemoral compartment and at least one tibiofemoral compartment.

- 35% had osteoarthritis only in the patellofemoral compartment

- Only 6% had osteoarthritis in one or both of the tibiofemoral compartments.

Other studies have reported similar findings, suggesting that unicompartmental tibiofemoral OA accounts for just 3-20% of all knee OA cases. This is interesting because up until recently the standard method for diagnosing osteoarthritis was with an X-ray of the knee performed from the front of the knee. This method, while quite effective at detecting osteoarthritis in the medial and lateral tibiofemoral compartments, completely obscures the patellofemoral compartment so this type of osteoarthritis was largely left undiagnosed. As a result, most of the knee braces designed for people with osteoarthritis focus on reducing the load on the most affected tibiofemoral compartment (usually the medial compartment) and redirecting it to the other tibiofemoral compartment. This means that most osteoarthritis knee braces are designed to fully address less than 20% of knee osteoarthritis cases. Knowing which variety of knee osteoarthritis you have and understanding the health of the 3 compartments of your knee can help inform decisions on treatments to pursue with your healthcare professional so you can better maintain your knee health.

How is severe osteoarthritis diagnosed?

Medical professionals can diagnose osteoarthritis in a number of ways but X-Rays and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) machines are two of the more common methods. X-rays and MRI’s are both used to help see the distance between the bones in the affected joint, and in the case of MRI’s, the state of the cartilage. X-Rays are fantastic at producing images of bone by using light that is invisible to our eyes but can pass through skin and other soft tissue but cannot pass through bone. This effect is also why the cartilage (which is comprised of softer tissue) cannot be seen in an X-ray so medical professionals will instead measure the space between the bones in the affected area. MRI Machines use powerful magnets that face different levels of resistance from the different materials in the body to deliver detailed “slices” of the observed area. These “slices” are high-resolution images that can show cartilage, bone and other types of tissue in much greater detail than an X-ray. MRI’s are however much more costly so their use is much less common depending on the severity of the condition as well as access.

Who can help?

As with any other medical issue it is best to consult a medical professional for their opinion on the best course of action for your knee. Seeing a doctor is always a good initial step if possible as they will best be able to provide guidance directly or point you in the right direction. In this section we will outline the different types of health care professionals that are commonly associated with the management of osteoarthritis.

General Practitioner

This would be your primary care doctor or family doctor in many cases. A General Practitioner (GP) is a great first place to help in assessing the situation. GPs are not usually specialized in treating osteoarthritis but are a great first line of defense and will be able to recommend more specialized health care professionals based on your particular needs.

Rheumatologist

As a specialist in rheumatic diseases like osteoarthritis, a rheumatologist would be someone who would possibly be brought in by a primary care doctor to help with advanced stages of osteoarthritis, or to help with special cases that a GP would be less equipped to help with.

Orthopedic Surgeon

An Orthopedic surgeon is a surgeon specializing in surgeries involving bones and related connective tissue. This type of surgeon becomes involved with osteoarthritis patients when surgery is being considered as part of a treatment plan, especially in late stage osteoarthritis. This would likely start as a consultation after being referred by a primary care physician.

Physiotherapist

Physiotherapists (or Physical Therapists) are medical professionals that focus on the movement of the body. Physiotherapists often work with people with osteoarthritis on low impact exercise routines to help promote mobility and minimize pain. They can also help with pre/post surgery recovery in many cases.

Physiatrist

Physiatrists are doctors that focus on physical rehabilitation through non-surgical means. They would be able to help with a treatment plan that includes exercise and physiotherapy, as well as medications. A primary care doctor may refer to a Physiatrist when surgery is ruled out as being part of the treatment plan that is best for a patient.

Occupational Therapist

Occupational therapists are experts in helping people minimize the impact of their conditions so they are still able to work and participate in other activities. Someone may seek out an occupational therapist if they are still active in the workforce and are having difficulties with advancing osteoarthritis symptoms that are limiting their ability to work.

Chiropractors

Specialists in the manual manipulation of the neck and back, chiropractors can help deal with pain in the neck and back that may arise from other osteoarthritis symptoms. It is not recommended that manual adjustments be performed on joints with active swelling so it is important to be sure that the chiropractor is aware of the medical history and conditions that the patient faces before therapies are administered.

Dietitian

A dietitian is an expert in tailoring a diet to suit specific medical needs. For someone with advanced osteoarthritis that may be a diet geared towards helping them lose weight or reducing inflammation. The inflammation reduction from diet may be more relevant to those with rheumatoid arthritis but following a similar diet is still said to link to a reduction in pain in some cases.

Osteopaths

Osteopaths are similar to chiropractors in that they specialize in the manual manipulation of the bones and joints to help improve function and lessen discomfort. They differ from chiropractors in that they take a more holistic approach than chiropractors with a broader focus.

What does this mean for my lifestyle and quality of life?

The impact of severe arthritis on quality of life is different for all people and there are many factors that help determine this. The severity of symptoms is one of the main factors in the impact of arthritis on your quality of life. If someone experiences less impacted mobility and less pain in general, their lifestyle would typically be affected to a lesser extent. Staying proactive when possible in trying to reduce the impact of various everyday activities can go a long way in maintaining your lifestyle. Working with a medical professional to find a suitable management plan for you, as well as being careful to follow that plan can also help to maintain quality of life. In this section, we will discuss some of the common challenges in the day-to-day life of someone impacted by late-stage knee arthritis.

Difficulty Squatting

As mentioned earlier squatting places forces on the knee that are many times greater than a person’s body weight. In advanced arthritis, this makes it much more difficult to squat due to the pain and stiffness in the affected joints. This can make performing household tasks, exercises or working more difficult.

Difficulty Climbing/Descending Stairs

Similarly to squatting, navigating stairs (both ascending and descending) can become challenging for someone due to pain and stiffness in the knee joint which is activated while using stairs. If the symptoms are not addressed to a point where this is manageable, accommodations must be made to limit the use of stairs when possible (changing the layout of a living space to keep as much as possible on one level is an example of this).

Difficulty Walking

As arthritis progresses, the ability to walk can become impaired when pain or stiffness in the affected joints reaches a sufficient level. Mobility assistance devices can be used to help maintain quality of life in cases where the symptoms are unable to be managed in other ways.

Pain

The above activities are often limited by the pain in the joints affected by arthritis. Having chronic pain can significantly reduce the overall quality of life in those affected if not adequately managed. Identifying movements or conditions that cause pain and limiting exposure to them is a natural response to this. Working with a medical professional on a treatment plan to address an increase in pain associated with arthritis is always the best option if possible.

Mental Wellbeing

Mental wellbeing is often affected by limited mobility or an increase in pain caused by arthritis. There is also a relationship between a negative state of mental wellbeing and an increase in symptom severity. This means that besides the straightforward relationship between increased pain and a decrease in mental wellbeing, there is also a link between a negatively impacted mental state and an increase in symptom severity.

Where to find info?

The internet has made it easier than ever to find a wealth of information on any topic. An unfortunate result of this is that it is also easier for misinformation to spread. It is recommended to look at anything you find online with a healthy dose of skepticism. When this information is relevant to your health it is especially important to try and narrow down your sources of information to those that use evidence-based research where possible. If the information you are researching contains links to relevant medical journals or is being provided by a trusted party (government, or a trusted authority on the topic like the Arthritis Society or Arthritis Foundation) that is usually a good sign. The best part of evidence-based research is that it changes as new evidence comes to light and you can be more confident in the timeliness and accuracy of the information you receive. As mentioned previously if you can contact a medical professional that would be the ideal place to start in this situation as they will best be able to assess your condition and determine your needs. It is also beneficial to do your own research and there are plenty of available resources to help with that. Arthritis-focused not for profit organizations are a fantastic resource with a wealth of information to offer.

What should I do now?

Now that you are armed with some information about your knees and how they are affected by arthritis you are in a great place to have a conversation with a health care professional to decide on some next steps for designing a treatment plan that can work for you. In our next piece in this series we outline the treatments currently used to treat arthritis so you can be better informed on what the treatments entail when discussing them with your doctor.

Terms and Abbreviations Used

OA: Osteoarthritis

Synovial Fluid: the natural lubricant that fills the joint to allow for smooth movements, keeps the joints separated, and lastly acts as a filter for the joint allowing the passage of nutrients while keeping out harmful substances.

Cartilage: the connective tissue found at the joints (and many other areas) in the body.

JSN: Joint Space Narrowing specifically in terms of the distance between the joints affected by OA

Medial tibiofemoral compartment: the inside part of the knee that faces the other knee

Lateral tibiofemoral compartment: the outside part of the knee that faces away from the other knee

Patellofemoral compartment: the front of the knee between the kneecap and thigh bone

Unicompartmental osteoarthritis: osteoarthritis that affects only one of the three compartments of the knee

Bicompartmental osteoarthritis: osteoarthritis that affects any two compartments of the knee

Tricompartmental osteoarthritis: osteoarthritis that impacts all three compartments of the knee

Osteophytes: growths of bone that often occur when the surrounding cartilage is worn away also known as “bone spurs”.

Varus Deformity: when the knee is bent outward, this is often referred to as bow-leggedness and can be caused by advanced OA

Valgus Deformity: when the knee is bent inward, this is often referred to as being knock-kneed and can be caused by advanced OA

References

- The Synovial Joint and Synovial Fluid, TRB Chemedica (UK) Ltd.

- What happens in osteoarthritis inside the synovial joint?, TRB Chemedica, 2016 Tom Greenway, What is the difference between Chiropractic & Osteopathy, THE WALDEGRAVE CLINIC

- D. T. Felson D. R. Gale M. Elon Gale J. Niu D. J. Hunter J. GogginsM. P. LaValley, Osteophytes and progression of knee osteoarthritis, Oxford Academic, Rheumatology, Volume 44, Issue 1, 1 January 2005, Pages 100–104

- M Englund, L S Lohmander, Patellofemoral osteoarthritis coexistent with tibiofemoral osteoarthritis in a meniscectomy population, Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1721–1726

- Living With Arthritis, the American Occupational Therapy Association, 2012

- Marshall Emig, MD, Arthritis Treatment Specialists, Veritas Health, 2011

- Marshall Emig, MD, Other Specialists for Arthritis Treatment, Veritas Health, 2011

- Marshall Emig, MD, Physiatrist for Arthritis Treatment, Veritas Health, 2011

- By Carolyn Sayre, How Chiropractors Can Help Arthritis Pain, Arthritis Foundation

- Physical Therapy for Arthritis, Arthritis Foundation

- Heather Browne BSc Dietitian, Sally Thomas BSc Dietitian, and Margaret Rayman, DPhil, RNutr, Diet and osteoarthritis, The British Dietetic Association, 2017

- William L. Porter, Jonisha P. Pollard, Mark S. Redfern, Forces and Moments on the Knee During Kneeling and Squatting, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Hospital for Special Surgery

- Anita E Wluka, Andrew Forbes, Yuanyuan Wang, Fahad Hanna, Graeme Jones, and Flavia M Cicuttini, Knee cartilage loss in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis over 4.5 years, National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Barton Wise, MD, et all, Psychological factors and their relation to osteoarthritis pain, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010 Jul; 18(7): 883–887.

- Barton L Wise, MD, MSc, et all, Patterns of Compartment Involvement in Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis in Men and Women and in Caucasians and African Americans: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Jun; 64(6): 847–852.

- Young-Mo Kim, MD, PhD and Yong-Bum Joo, MD, PhD, Patellofemoral Osteoarthritis, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012 Dec; 24(4): 193–200.

- Kevin R. Vincent, M.D., Ph.D., Bryan P. Conrad, Ph.D., Benjamin J. Fregly, Ph.D., and Heather K. Vincent, Ph.D., The Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis: A Mechanical Perspective on the Knee Joint, National Center for Biotechnology Information, PM R. 2012 May; 4(5 0): S3–S9.

- Nalbant S1, Martinez JA, Kitumnuaypong T, Clayburne G, Sieck M, Schumacher HR Jr., Synovial fluid features and their relations to osteoarthritis severity: new findings from sequential studies., National Center for Biotechnology Information, Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003 Jan;11(1):50-4.

- McAlindon TE1, Snow S, Cooper C, Dieppe PA.,Radiographic patterns of osteoarthritis of the knee joint in the community: the importance of the patellofemoral joint, National Center for Biotechnology Information,.Ann Rheum Dis. 1992 Jul;51(7):844-9.

- Duncan RC1, Hay EM, Saklatvala J, Croft PR., Prevalence of radiographic osteoarthritis--it all depends on your point of view., National Center for Biotechnology Information, Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 Jun;45(6):757-60.

- Peterfy C1, Kothari M., Imaging osteoarthritis: magnetic resonance imaging versus x-ray, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006 Feb;8(1):16-21.

- Hinman RS1, Lentzos J, Vicenzino B, Crossley KM., Is patellofemoral osteoarthritis common in middle-aged people with chronic patellofemoral pain?, National Center for Biotechnology Information, Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014 Aug;66(8):1252-7.

- Osteophyte (bone spur), NHS, 2016.

- James Udell, Osteoarthritis, American College of Rheumatology, 2017.

- F.Berenbaum, Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!), Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Volume 21, Issue 1, January 2013, Pages 16-21.

- N.E.Lankhorst, J.Damen, E.H.Oei, J.A.N.Verhaar, M.Kloppenburg‖, S.M.A.Bierma-Zeinstra, M.van Middelkoop, Incidence, prevalence, natural course and prognosis of patellofemoral osteoarthritis: the Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee study, Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Volume 25, Issue 5, May 2017, Pages 647-653.

- Heekin, R. D., & Fokin, A. A. (2014). Incidence of bicompartmental osteoarthritis in patients undergoing total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: is the time ripe for a less radical treatment?. The journal of knee surgery, 27(01), 077-082.

- Shahid, M. K., Al-Obaedi, O., & Shah, M. (2018). Prevalence of compartmental osteoarthritis of the knee in an adult patient population: A retrospective observational study. EC Orthopaedics, 9(10), 774–780.